Statistical forecasting is a method of predicting future outcomes based on the analysis of historical data and statistical models.

Statistical forecasting uses patterns identified in time series (trends, seasonality, cyclicality) to extrapolate them into the future and estimate possible outcomes. Key methods include extrapolation, linear regression, exponential smoothing, and autoregression.

The desire to look beyond the time horizon, to anticipate the course of events, and to minimize risks is a fundamental human need across various spheres of activity. Intuitive guesses and subjective assessments have been replaced by a rigorous scientific discipline that allows turning accumulated data arrays into substantiated judgments about the future. This discipline is based on the laws of probability theory and mathematical statistics, providing a toolkit for trend analysis and building predictive models. What is statistical forecasting if not a bridge between past experience, recorded in numbers, and a probabilistic picture of impending changes? This approach has become the cornerstone for making balanced decisions under conditions of uncertainty, characteristic of the modern world.

What is Statistical Forecasting?

The essence of this scientific and practical field lies in extrapolating the patterns, interrelationships, and trends identified in past data onto future periods. It is based on the premise that many processes, especially in the socio-economic sphere, possess a certain inertia. Forecasting based on statistical data begins with the collection and thorough preprocessing of information, which serves as the empirical foundation for subsequent analysis. A critically important stage is assessing the quality and representativeness of data, as “garbage in” will inevitably lead to erroneous conclusions out.

The procedure for building a forecast is never purely mechanical. An analyst must understand the nature of the phenomenon under study to correctly interpret the results and choose adequate methods. For instance, an attempt to apply linear regression to data with seasonal fluctuations or cyclical crises is doomed to failure. As the noted statistician George Box remarked, “all models are wrong, but some are useful“1A quote by George Box, a British statistician, emphasizing that a model is a simplified representation of reality, and its value lies in practical applicability, not in absolute truth.. This statement perfectly illustrates the philosophy of the approach: the goal is not absolute accuracy, but obtaining a sufficiently reliable and useful estimate that reduces uncertainty.

A financial analyst using these principles to assess the future return on assets, or a marketer forecasting demand for a new product—both apply the same logic. They proceed from the assumption that historical patterns, adjusted for known changes in conditions, can serve as a guide. Thus, this type of analysis turns data from a passive archive into an active strategic asset, allowing not just to react to changes, but to prepare for them in advance.

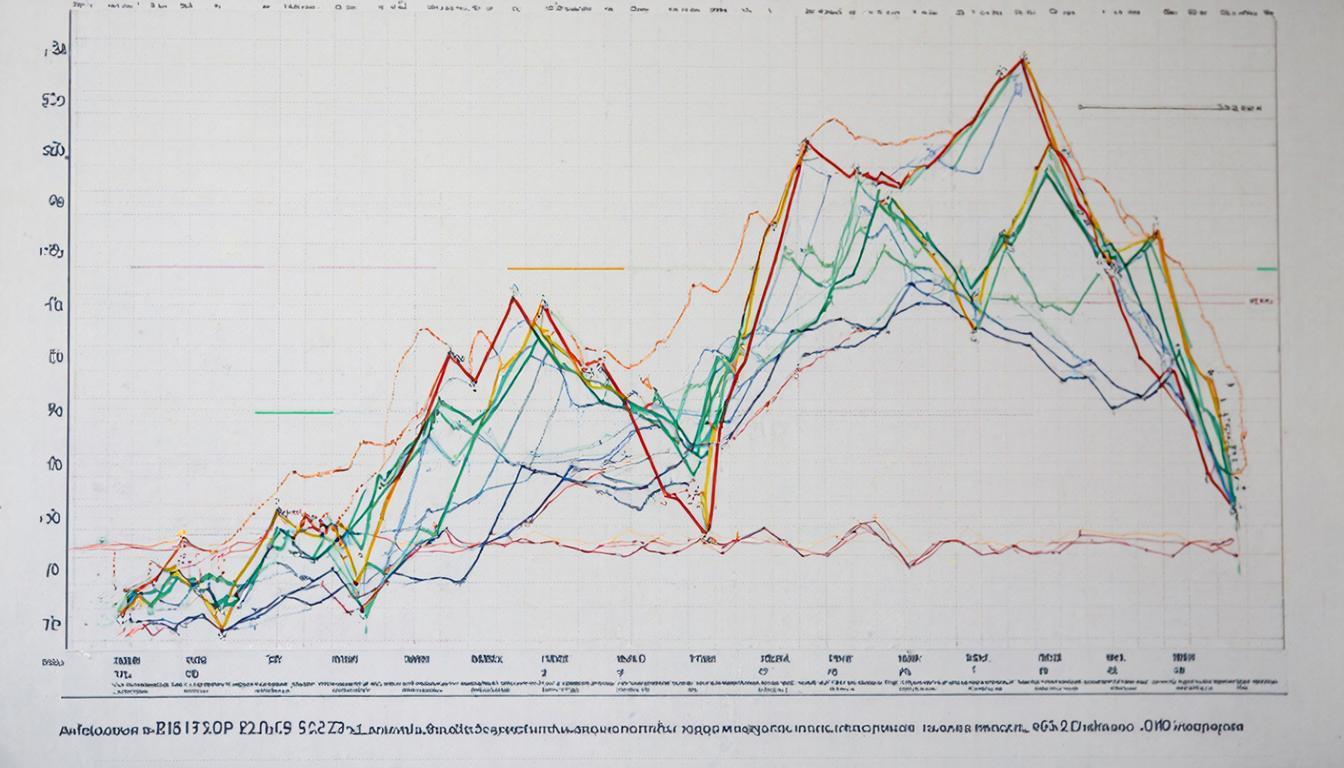

In my practice, I have repeatedly encountered situations where a simple visual examination of time series graphs provided a primary hypothesis about the presence of a trend or seasonality. However, it was the subsequent application of formal statistical tests, such as a stationarity check or analysis of the autocorrelation function, that separated random fluctuations from significant patterns. This synthesis of expert knowledge and formal methods constitutes the core of effective predictive modeling.

Basics of Statistical Forecasting

Any path to building a reliable prediction rests on several unshakable principles. The first of these is the principle of inertia, assuming that the development of a phenomenon is largely determined by established conditions and trends. The second principle is adequacy, requiring that the chosen mathematical model most accurately reflects the essential properties of the real object. The third key principle is alternativeness, which implies the development of several scenarios (optimistic, pessimistic, baseline) depending on the variation of input parameters or assumptions.

The central concept in this field is a time series—a sequence of measurements of some indicator, ordered in time (e.g., monthly sales volumes, daily stock quotes, annual inflation levels). Analyzing such a series is the first step. The researcher looks for its components: long-term trend (trend component), recurring fluctuations of a fixed periodicity (seasonal component), cyclical changes associated with economic cycles, and random, unsystematic disturbances (residual component or “noise“). The basics of statistical forecasting teach how to decompose a complex signal into these components to understand its nature.

No less important is the concept of forecast accuracy and reliability. No method can provide a one hundred percent correct result, so the outcome of the work is always an interval estimate. The forecast is presented as a “fork”—a point value and a confidence interval that, with a given probability (e.g., 95%), will cover the actual future value. The width of this interval speaks to the uncertainty of the forecast: the larger it is, the more cautiously one should treat the results. The ability to correctly assess and interpret this uncertainty is a mark of an analyst’s professionalism.

Modern approaches also require an understanding of the stationarity of a time series. A stationary series is one whose properties (mean value, variance) do not depend on the observation time. Many classical methods, such as autoregression models, work specifically with stationary data. If a series is non-stationary (e.g., has a pronounced upward trend), it must be transformed, often by taking differences between successive observations. This process, called differencing, is a standard technique in the specialist’s arsenal.

Types of Statistical Forecasting

The classification of forecasting methods is extensive and depends on various criteria. One of the main ones is the forecasting horizon. Short-term forecasts (up to a year) are critically important for operational management, such as inventory control. Medium-term forecasts (1-3 years) are used for business planning and budgeting. Long-term forecasts (over 3 years) serve as the basis for strategic planning and investment programs. Accuracy is generally inversely proportional to the horizon: it’s easier to predict tomorrow’s weather than the weather a month from now.

Based on the type of data used and the approaches, two large groups of methods are distinguished. The first is extrapolation methods, which extend an identified past trend into the future. They are relatively simple and effective for stable processes. The second group is causal (cause-and-effect) methods, or regression analysis models. They do not simply extrapolate the trend but attempt to explain the behavior of the predicted variable (dependent) through the influence of other factors (independent variables). Types of statistical forecasting also include expert assessments, which formalize specialists’ opinions, but they are considered more qualitative rather than strictly quantitative methods.

- Extrapolation methods: moving averages, exponential smoothing (simple, Holt, Holt-Winters), growth curves.

- Causal methods: simple and multiple linear regression, nonlinear regression models, econometric systems of equations.

- Time series analysis methods: ARIMA models 2ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) is a statistical model for analyzing and forecasting time series. It consists of three parts: autoregressive (AR), integrated (I), and moving average (MA), each with its own parameter (p, d, q). The model uses past data to forecast future values and can be applied when the time series is not stationary (i.e., its mean and variance change over time). (autoregressive integrated moving average), SARIMA 3SARIMA (Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) is an extension of the ARIMA model used for analyzing and forecasting time series data with seasonal patterns. The model accounts for both non-seasonal and seasonal components, allowing for more accurate forecasting of, for example, retail sales, electricity consumption, or tourist flow, which show repeating patterns at certain intervals. (accounting for seasonality), ARCH/GARCH 4ARCH and GARCH are econometric models for time series analysis, standing for “Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity” (ARCH) and “Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity” (GARCH). They are used to model the volatility of financial markets, i.e., periods of high and low variability that follow one another. (for the volatility of financial data).

The choice of a specific type depends on the research objectives, the nature of the data, the required accuracy, and available computing resources. In practice, a combination of methods is often applied, and the final forecast is formed as a weighted average of results obtained by different methods. This approach, called ensemble forecasting, allows compensating for the shortcomings of some models with the advantages of others and increases overall reliability.

Modeling Statistical Forecasting

The process of building a predictive model is an iterative cycle that can be described by a sequence of key stages. The starting point is a clear statement of the problem: what exactly needs to be forecasted, with what accuracy, and for what period. Next comes the collection of historical data, their cleaning from anomalies (outliers) and gaps, as well as visual and preliminary statistical analysis. This stage often takes up to 80% of all work time, but skipping it negates all further efforts.

The next step is choosing a family of models that are theoretically suitable for this type of data. For example, for a series with obvious seasonality, it is logical to try the Holt-Winters model or SARIMA. After selection, the model parameters are estimated based on historical data using special algorithms (e.g., maximum likelihood method or OLS for regression). Modeling statistical forecasting enters a crucial phase when the built model needs to be tested for adequacy.

Model verification includes analyzing the residuals—the differences between actual values and values predicted by the model for the past period. Residuals should behave like “white noise“: be random, have no autocorrelation, and no systematic patterns. The presence of structure in the residuals signals that the model failed to capture some pattern, and it needs to be made more complex or another one should be chosen. Also, splitting the sample into training (on which parameters are estimated) and testing (on which forecast accuracy is checked) is used to avoid overfitting—a situation where the model perfectly describes history but predicts the future poorly.

After successful verification, the model is ready to generate forecast values. However, the work does not end there. The real world is dynamic, and the conditions under which the model was built can change. Therefore, an effective forecasting system requires constant monitoring. Special tracking signals help detect in time when actual values begin to systematically deviate from the predicted ones, which indicates the need for revision or re-evaluation of the model. Thus, forecasting by statistical analysis is not a one-time action but a continuous process of supporting decision-making.

Statistical Forecasting Methods in Economics

The economic sphere is perhaps the most fruitful and in-demand testing ground for the application of predictive models. The accuracy of estimates influences central bank decisions, state budgets, corporate investment strategies, and even the well-being of citizens. Statistical forecasting methods in economics cover a wide range of tasks: from predicting macroeconomic indicators like GDP, unemployment, and exchange rates to microeconomic forecasts of demand for a specific product in a particular region.

One of the cornerstones of macroeconomic analysis is econometrics—a discipline at the intersection of economics, statistics, and mathematics. Econometric models are systems of interrelated regression equations that describe the functioning of entire industries or the economy as a whole. An example could be a model assessing the impact of a central bank’s key rate on inflation and investment activity. These models, being extremely complex, allow for scenario analysis: “what if…“.

At the company level, demand and sales forecasting methods are most common. Here, relatively simple exponential smoothing methods, adapting to trend changes, as well as complex regression models, accounting for the influence of price, advertising costs, competitor actions, seasonality, and even weather conditions, find application. Accurate demand forecasting directly impacts logistics, inventory management, production planning, and ultimately financial results. I had the opportunity to participate in a demand forecasting project for a retail network, where adding factors of promotional activities and calendar events to the model reduced the forecast error by 15%, leading to significant savings on warehouse costs.

Another critically important direction is forecasting in financial markets. Time series analysis of quotes, volatility, and trading volumes attempts to find patterns that allow generating income. ARIMA models for prices and ARCH/GARCH for assessing risks associated with market variability are widely used. However, the well-known efficient market hypothesis comes into play here, which calls into question the possibility of consistently making excess profits based on public historical information. Nevertheless, the methods are used to estimate Value at Risk (VaR) 5Value at Risk (VaR) is a quantitative estimate of the maximum possible loss for an investment portfolio or a single asset with a given probability over a certain period of time. For example, if the monthly VaR is $1 million at a 95% confidence level, it means there is 95% confidence that losses during the month will not exceed $1 million. and for stress testing portfolios.

Statistical Methods for Forecasting Inflation

Inflation is a key macroeconomic indicator, the stability of which is the goal of most central banks worldwide. Forecasting the dynamics of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) lies at the heart of monetary policy. Statistical methods for forecasting inflation are highly complex, as this indicator depends on numerous interrelated factors: monetary (money supply, interest rates), fiscal (government spending, taxes), external economic (exchange rates, import prices), and inflation expectations of the population and businesses.

Traditionally, two groups of models are used. The first is based on direct extrapolation of historical inflation data, possibly accounting for seasonality (e.g., price increases before holidays). These models, such as ARIMA, can be quite accurate over short horizons but often fail to capture turning points caused by changes in economic policy or supply shocks. The second, more common group is structural models that attempt to explain inflation through its fundamental drivers.

In structural models, inflation is often represented as a function of the GDP gap (deviation of actual output from potential), growth in the money supply, exchange rate dynamics, and an inertial component (inflation of the previous period). Multiple regression methods are used to estimate such models. Vector autoregression (VAR) models are also widely used, allowing for the analysis of dynamic interaction of the entire system of macroeconomic indicators without rigidly specifying cause-and-effect relationships a priori. Modern central banks rely on complex DSGE models 6DSGE model (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium) is a modern macroeconomic method used to analyze and forecast business cycles and policy by modeling the behavior of economic agents at the micro level and accounting for various stochastic “shocks.” Models of this type are used by central banks and financial institutions to assess macroeconomic policy, explain historical data, and forecast economic indicators. (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium models), which represent the pinnacle of econometric modeling.

A special role is played by forecasting inflation expectations, which themselves become self-fulfilling prophecies. For their assessment, both survey methods (surveys of businesses and the population) and indirect methods based on analyzing the difference in yields between regular and inflation-indexed bonds are used. Accounting for this psychological factor is one of the most complex challenges for analysts. An accurate inflation forecast allows central banks to adjust their policies in a timely manner, ensuring price stability, which is the key to sustainable economic growth in the long term.

📝

- 1A quote by George Box, a British statistician, emphasizing that a model is a simplified representation of reality, and its value lies in practical applicability, not in absolute truth.

- 2ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) is a statistical model for analyzing and forecasting time series. It consists of three parts: autoregressive (AR), integrated (I), and moving average (MA), each with its own parameter (p, d, q). The model uses past data to forecast future values and can be applied when the time series is not stationary (i.e., its mean and variance change over time).

- 3SARIMA (Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) is an extension of the ARIMA model used for analyzing and forecasting time series data with seasonal patterns. The model accounts for both non-seasonal and seasonal components, allowing for more accurate forecasting of, for example, retail sales, electricity consumption, or tourist flow, which show repeating patterns at certain intervals.

- 4ARCH and GARCH are econometric models for time series analysis, standing for “Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity” (ARCH) and “Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity” (GARCH). They are used to model the volatility of financial markets, i.e., periods of high and low variability that follow one another.

- 5Value at Risk (VaR) is a quantitative estimate of the maximum possible loss for an investment portfolio or a single asset with a given probability over a certain period of time. For example, if the monthly VaR is $1 million at a 95% confidence level, it means there is 95% confidence that losses during the month will not exceed $1 million.

- 6DSGE model (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium) is a modern macroeconomic method used to analyze and forecast business cycles and policy by modeling the behavior of economic agents at the micro level and accounting for various stochastic “shocks.” Models of this type are used by central banks and financial institutions to assess macroeconomic policy, explain historical data, and forecast economic indicators.