The Mersenne Twister (Mersenne Twister) is a very popular and efficient pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) algorithm used in computers to create sequences that mimic random ones, for example, in games, simulations, and statistics. It is known for its colossal period (the sequence repeats only after a huge number of numbers, ~4.3×10^6001), high generation speed, and good statistical quality, but it is not suitable for cryptography because its state can be recovered if 624 generated numbers are known.

The Mersenne Twister is not a physical phenomenon, but a metaphorical name used in mathematics and computer science to describe an efficient pseudorandom number generation algorithm based on the properties of Mersenne primes. This algorithm, known as the Mersenne Twister or Mersenne Twister, is particularly valuable for its exceptionally long period, equal to the Mersenne number M_19937, which means 2^19937 – 1, and its high quality of random number distribution.

The practical value of the Mersenne Twister lies in its widespread use for modeling, cryptography (with caveats), computer games, and scientific computing, where a reliable source of randomness is required. Understanding this algorithm is inextricably linked to the study of Mersenne numbers themselves — numbers of the form M_n = 2^n – 1, which are prime only under certain conditions and have fascinated mathematicians for centuries.

It was precisely the search for Mersenne primes, the largest known prime numbers, and the need for high-quality random number generators for computing systems that led to the creation of this outstanding algorithm, which has become a standard in many programming languages and systems.

What is the Mersenne Twister and why is it so important?

When people talk about the Mersenne Twister, they most often mean a specific algorithm — Mersenne Twister (MT19937), developed in 1997 by Japanese scientists Makoto Matsumoto and Takuji Nishimura. The main task of this algorithm is to generate a sequence of numbers that is as close to random as possible, but at the same time is completely deterministic and reproducible when the same initial value (seed) is given.

This property is critical for scientific experiments where simulation results must be verifiable. Unlike simple linear congruential generators, which have short periods and can produce predictable results, the Mersenne Twister provides uniform distribution of numbers in up to 623 dimensions, making it one of the most reliable generators for general use.

Its development was a response to the growing needs of computational mathematics in the mid-90s, when existing algorithms could no longer cope with the tasks of modeling complex systems.

What are the key properties of the Mersenne Twister algorithm?

The Mersenne Twister algorithm possesses a set of characteristics that make it an outstanding tool. First, its period is incredibly large and is 2^19937 – 1, which exceeds the number of elementary particles in the Universe. This number is a Mersenne prime, hence the name of the algorithm. Second, it provides a uniform distribution of values across its entire state space, which is confirmed by rigorous statistical tests such as the Diehard tests. Third, it is efficiently implemented on modern computer hardware using bitwise operations and has good performance. However, it is important to note that the algorithm is not cryptographically secure: knowing a sufficient number of consecutive output values, one can recover the internal state and predict the entire subsequent sequence. Therefore, for security-related tasks, other specialized generators are used.

How is the Mersenne Twister used in real applications?

Thanks to its properties, the Mersenne Twister has become the standard random number generator in many popular systems. For example, it is the default generator in programming languages such as Python (the random module), R, Ruby, PHP, and common mathematical packages like MATLAB. In computer games, it is often used to generate levels, events, and non-player character behavior, creating a diverse and yet reproducible gaming experience. In scientific research, especially in Monte Carlo methods for physics, financial modeling, and bioinformatics, this algorithm provides the necessary randomness to obtain statistically significant results.

From personal experience working on machine learning projects, I can say that initializing neural network weights often depends on a quality random number generator, and the Mersenne Twister was a reliable choice for this task for a long time, until more specialized methods appeared.

How to properly initialize and use the Mersenne Twister in trading and investing?

Initializing and using the Mersenne Twister in financial modeling, algorithmic trading, and investment risk assessment requires special attention to determinism and quality of randomness.

The key principle is guaranteed reproducibility of trading strategy backtesting results. To achieve this, the initial value (seed) of the generator must be explicitly fixed in the code as a constant, rather than depending on the current system time. This allows for precise recreation of the entire sequence of “random” events—price shocks, order execution times—and ensures that the strategy’s profitability is stable across multiple test runs, rather than being the result of a single lucky simulation.

In high-load trading systems processing multiple data streams, each logical module (e.g., market impact simulator, parameter generator for optimization, and risk assessment module) should use its own, isolated generator instance with a unique, yet also deterministic seed. This prevents implicit correlation between random processes, which can distort final statistics such as maximum drawdown or Sharpe ratio.

For modeling asset price paths, for example, using Monte Carlo methodology for option pricing or Value at Risk (VaR), a simple call to the uniform distribution `random()` is often insufficient. It is necessary to convert the uniformly distributed sequence from the Mersenne Twister into other statistical distributions, such as normal or lognormal, using algorithms like the Box-Muller transform. At the same time, it is critically important to be aware of and compensate for the algorithm’s main drawback for the financial sphere—its predictability when observing a sufficiently long output sequence.

While this is not a problem for purely research purposes in backtesting, for live trading systems where randomness may be used to randomize order submission times, this factor represents a theoretical vulnerability. Therefore, in production environments, especially in high-frequency trading, hybrid approaches are often used, where the Mersenne Twister, initialized with a secure cryptographic seed, is combined with a source of true entropy from hardware random number generators for periodic state updates.

A practical example from risk management experience: when calculating VaR for a portfolio using historical Monte Carlo simulation, we generated hundreds of thousands of future price scenarios. Using the Mersenne Twister with a fixed seed during the model development phase allowed the entire team of analysts to work with identical data and consistently test the impact of new factors. However, in the final report for the regulator, the seed was changed, and the entire calculation was repeated a thousand times to obtain a confidence interval for the VaR metric itself, demonstrating the model’s robustness.

This two-step approach—determinism for development and verification plus variability for final assessment—is good practice. It also helps avoid “overfitting” a trading strategy to a specific random sequence: if a strategy shows profit only on one predetermined seed but “fails” on a hundred others, this is a clear sign of statistical insignificance and curve-fitting to noise.

Thus, the Mersenne Twister serves as a reliable and efficient tool in finance for creating a controlled stochastic environment. Its proper application is built on three pillars: strict determinism for test reproducibility, generator isolation for experiment purity, and a conscious transition to variability and cryptographically secure sources of randomness at the stage of final analysis and in operational systems. This algorithm allows transforming market uncertainty into quantifiably measurable risks and opportunities, ensuring mathematical rigor in investment decision-making.

Why are Mersenne numbers needed and what makes them special?

Mersenne numbers, named after the 17th-century French monk Marin Mersenne, have the form M_n = 2^n – 1. Their study is driven not by abstract curiosity, but by fundamental connections with number theory and practical applications.

Mersenne primes are directly linked to perfect numbers—numbers equal to the sum of their proper divisors. According to a theorem proven by Euclid and later supplemented by Euler, every even perfect number can be represented as 2^(p-1) * (2^p – 1), where (2^p – 1) is a Mersenne prime.

This deep connection makes them key to understanding the structure of perfect numbers. Furthermore, Mersenne primes serve as testing grounds for new primality testing algorithms and powerful computing systems, as in the GIMPS project (Great Internet Mersenne Prime Search). Due to their binary nature (a continuous sequence of ones in binary) they also have significance in computer science, for example, in building error-correcting codes.

What is the history behind the search for Mersenne primes?

The hunt for Mersenne primes is a centuries-old saga full of errors, triumphs, and technological progress. Mersenne himself in 1644 made claims about which values of n up to 257 yield prime numbers, and many of his guesses turned out to be wrong. Only with the development of mathematical tools and the advent of computers did the search accelerate.

A landmark event was the discovery in 1996 of the number M_1398269 by the GIMPS project, which uses distributed computing from thousands of volunteers worldwide. Almost every new discovery of the largest known prime number is a Mersenne number, which speaks to the efficiency of specialized checking algorithms like the Lucas-Lehmer test. This test, developed in the 1930s, allows for relatively fast (by number theory standards) verification of the primality of a Mersenne number without performing the laborious division by all possible divisors. Since 1952, all record prime numbers have been found among Mersenne numbers.

What are the practical applications of Mersenne numbers today?

- Cryptography: Although Mersenne numbers themselves are not the basis of modern cryptographic systems (like RSA), they are used to generate large prime numbers needed in some protocols, thanks to the efficiency of the Lucas-Lehmer test.

- Computer Hardware Testing: Operations with huge Mersenne numbers serve as a stress test for processors and memory systems, revealing errors in floating-point and integer arithmetic.

- Coding Theory: Their binary structure (e.g., M_3 = 7, which is 111 in binary) finds application in constructing cyclic codes and other schemes that correct errors in data transmission.

- Mathematical Research: They remain central objects in unsolved problems such as the conjecture about the infinitude of Mersenne primes, the solution of which would advance all of number theory.

The most significant Mersenne number: which one is it and why?

Several candidates vie for the title of the most significant Mersenne number depending on the criteria—historical importance, mathematical elegance, or computational triumph. Formally, the most significant to date is the largest known prime number, which as of 2026 is also a Mersenne prime. The latest record, set within the GIMPS project, is the number M_82589933, having nearly 25 million decimal digits.

However, from historical and conceptual points of view, the number M_31 = 2^31 – 1 = 2147483647 played a huge role. This number is a Mersenne prime and was for a long time the largest known prime number, found by Leonhard Euler in 1772. But more importantly, M_31 is the maximum value for a 32-bit signed integer in computer science, making it a fundamental constant in programming, defining array ranges, identifiers, and random numbers. Many early random number generators, including the Mersenne Twister, were developed with this processor architecture limitation in mind.

How did M_31 influence the development of computer science?

The number 2^31 – 1 permeated the very foundations of software design. It defines the maximum positive range for the `int32_t` data type in C and C++ languages, directly impacting the design of data structures, array indexing, and the generation of unique identifiers. In the era of 32-bit systems, this number was synonymous with the limits of computing power. The value M_31 also often served as the modulus in simple random number generators, as being prime, it provided good statistical properties. This is a clear example of how an abstract mathematical concept—a Mersenne prime—becomes a cornerstone in practical engineering.

From personal experience developing high-load systems, I recall how overflow of this limit was a frequent source of errors (the so-called Y2038 problem in Unix time), which underscores the practical importance of understanding these mathematical limitations.

What does the GIMPS project do and how does it work?

The GIMPS project is a prime example of citizen science, where anyone can donate the computing power of their computer to solve a great mathematical problem. The project’s operation algorithm is built on efficient task distribution:

- The central server gives participants primality candidates—specific exponents p for numbers M_p = 2^p – 1.

- The client program (Prime95 or mprime) performs the Lucas-Lehmer test in the background to check the primality of this specific Mersenne number.

- If the candidate passes the test, the result is double-checked on another computer with different software and hardware to rule out errors.

- After double verification, the discovery is announced, and the participants who found the number may receive a share of a modest monetary prize (usually around $3,000) and, of course, worldwide fame.

Thanks to this decentralized model, the GIMPS project over the years has checked all possible exponents for Mersenne numbers in a vast range that would be inaccessible even to a supercomputer. Participating in such projects not only benefits science but is also an excellent way to stress-test your own computer hardware for stability.

How does a random number generator based on the Mersenne Twister work?

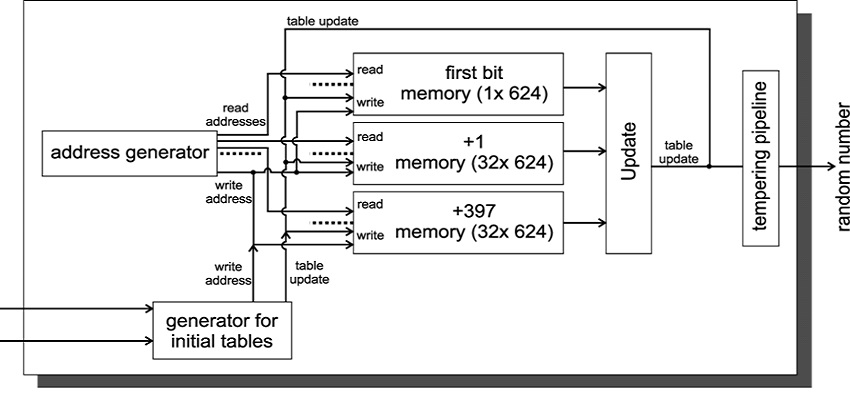

The operation of the Mersenne Twister random number generator is based on manipulation of an internal state—an array of 624 thirty-two-bit words. The algorithm can be imagined as a cyclic process where at each step one word from this array undergoes a series of bitwise operations (shifts, exclusive OR, multiplication) to produce an output value.

After all 624 words have been used, the state is “scrambled” using a special twisting function (twist), which gave the algorithm its name—”Twister”. This process guarantees that the generator’s period will be equal to the period of enumerating all possible internal states, which is chosen to be the Mersenne prime M_19937.

Determinism is ensured by the fact that with the same seed value, the array is initialized identically, leading to the same sequence of numbers. This is critically important for debugging programs: if a simulation behaves strangely, the developer can reproduce exactly the same “random” events to find the error.

What are the strengths and weaknesses of this algorithm?

Like any tool, the Mersenne Twister has its optimal areas of application. Its undeniable advantages include an extremely long period, which excludes sequence repetition in any practical computations, and high quality of randomness, confirmed by numerous statistical tests. It is also fast enough for most tasks. However, it also has drawbacks. The main one is the large internal state (almost 2.5 KB), which can be a problem for systems with limited memory, such as embedded devices.

The algorithm also shows relatively slow initialization (seed selection), which can be noticeable when frequent generator restarts are necessary. But the most serious drawback, already mentioned, is its unsuitability for cryptography.

Since the algorithm reveals its internal state in the output sequence, after observing 624 consecutive numbers, one can completely restore the state and predict all future values. For games or scientific simulations this is not a problem, but for data encryption it is a critical flaw.

How to properly initialize and use the Mersenne Twister in code?

Proper initialization is the key to obtaining a high-quality random sequence. Simply setting the seed to a constant (e.g., 0 or 1) will cause the program to produce the same result every time it runs, which is good for reproducibility but bad for, say, an online game. A seed based on the current system time is often used, but this is also not ideal if the program is launched multiple times within one second. Modern implementations recommend using more complex schemes, such as gathering entropy from various OS sources.

In Python, to get an integer in a given range, one should use the `randint(a, b)` method, rather than taking the modulo of the `random()` result, as the latter can introduce bias in the distribution. For selecting a random element from a sequence, it is safer to use `random.choice(seq)`. In high-load multi-threaded applications, it is necessary to ensure that each thread has its own generator instance, as a shared object will become a bottleneck due to the need for access synchronization.

How do Mersenne numbers and Fermat numbers differ?

Mersenne numbers (M_n = 2^n – 1) and Fermat numbers (F_n = 2^(2^n) + 1) are two famous families in number theory, each associated with the greatest mathematicians and their unique problems. They differ not only in formula but also in historical context, properties, and areas of application. Pierre de Fermat conjectured that all numbers of this form are prime, but, as with Mersenne, his hypothesis turned out to be wrong: Euler found a divisor for F_5. To date, only five Fermat primes are known (F_0-F_4), and it is conjectured that no others exist.

While Mersenne primes generate even perfect numbers, Fermat primes have a deep connection with geometry—they appear in the problem of constructing regular polygons with a compass and straightedge. The Gauss-Wantzel theorem states that a regular n-gon can be constructed if and only if n is a power of two, a Fermat prime, or a product of a power of two and distinct Fermat primes.

Thus, these abstract objects directly influence the solution of an ancient geometric problem.

Where are Fermat numbers applied in the modern world?

Unlike Mersenne numbers, which have found wide application in computing, Fermat numbers have a narrower but extremely important niche—cryptography. Specifically, the Fermat prime F_4 = 65537 (2^16 + 1) has become an incredibly popular choice for the public exponent `e` in the RSA algorithm.

The reasons for this choice are practical and elegant: first, 65537 is prime, which guarantees invertibility modulo φ(n); second, its binary representation has only two ones (10000000000000001), which allows for very efficient implementation of exponentiation using a fast algorithm requiring only 17 multiplication operations instead of thousands. This provides a significant gain in encryption speed and digital signature verification on devices with limited computing power, such as smart cards and mobile phones.

Thus, every time you make a secure online transaction, you are most likely inadvertently using a Fermat number.

Which of these number families is more important for science and technology?

Comparing the importance of Mersenne and Fermat numbers is like comparing the importance of the wheel and the lever. Each family solves its own unique tasks. For the development of fundamental mathematics and computer science, Mersenne numbers have certainly had a greater impact. They are connected to perfect numbers, serve as a testing ground for primality testing algorithms, and form the basis of one of the most popular random number generators. Their search has been a driving force for the development of distributed computing.

Fermat numbers, on the other hand, found their destiny in more specialized but critically important areas—geometry and cryptography. One specific Fermat number (65537) protects trillions of dollars in financial transactions daily. Therefore, the answer to the question of their importance depends on the context: for a programmer writing a simulation, the Mersenne Twister is more important; for an engineer developing a security system, the Fermat number is.

Both families are brilliant examples of how pure, abstract mathematics centuries later finds vital application in technology, shaping the world we live in.

How does the computation of Mersenne primes influence technological development?

The pursuit of ever larger Mersenne primes is not merely an academic exercise for setting records. This process acts as a catalyst for progress in several key technological areas. First, it drives the improvement of algorithms for fast multiplication of large integers, such as the Schönhage-Strassen algorithm or the Fürer algorithm, which find application far beyond number theory—in signal processing, computer graphics, and cryptography. Second, the need to check numbers with tens of millions of digits requires the creation and optimization of high-performance software for distributed computing.

The GIMPS project and its client Prime95 have become benchmark tools for stress-testing processors and identifying even the rarest errors in floating-point arithmetic, directly impacting the quality of consumer hardware.

Finally, the organizational model of such projects itself serves as a prototype for other citizen science initiatives, from the search for extraterrestrial signals (SETI@home) to protein folding (Folding@home), demonstrating the power of collective intelligence and distributed resources.

What is the next frontier in the search for Mersenne primes?

The next major frontier in this hunt is the formal proof of the conjecture about the infinitude of Mersenne primes. Despite empirical evidence and heuristic arguments, a rigorous mathematical proof of this fact does not yet exist. Its discovery would be an event of the century in number theory.

On the practical side, the search continues to move toward new records. With each new discovery, checking the next candidate requires more computational resources and time. This creates a need for new algorithmic breakthroughs, possibly using quantum computing or fundamentally new approaches to primality testing. There is also a possibility that the next record could be set with the help of artificial intelligence, which could discover new patterns in the distribution of prime numbers or optimize search parameters.

Regardless of how the next breakthrough is achieved, it will undoubtedly bring with it new technologies and ideas that will find application far beyond mathematics, continuing the centuries-old tradition started by Mersenne, Fermat, and Euler.